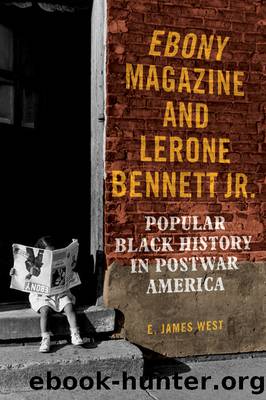

Ebony Magazine and Lerone Bennett Jr. by E. James West

Author:E. James West

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Published: 2020-09-14T16:00:00+00:00

From the Margins to the Mainstream

During its first two decades in print, Ebony’s black history content had fed into the first phase of the postwar “black history revival” identified by scholars such as Vincent Harding. The initial impetus for this “revival” stemmed mainly from grassroots educational activists, with localized demands for curricular reform and greater historical representation catalyzing community activism across the country.7 The black press documented these efforts, with many black periodicals attempting to address community concerns directly through the creation of new history-themed features and series that sought to disseminate black history content to a mass audience. From a similar perspective, black scholars pushed for what John Hope Franklin described as a “new Negro history,” which demanded “the same justice in history that is sought in other spheres.”8

In cities such as Detroit, protests against the continued use of racially biased textbooks by school boards and commissions prompted the creation of supplementary teaching materials that offered a more representative account of black history.9 Efforts to democratize representations of black history within the public sphere were also rewarded with small victories. Pressure from black activists on both the local and federal levels meant that some efforts were made to include black perspectives in centennial commemorations of the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation. In Chicago, groups such as the National Conference of Negro Artists looked to reclaim public narratives of slavery and abolition.10 In the South, African American leaders pushed back against white segregationists and their glorification of the Confederacy by promoting emancipationist readings of the conflict.11

Despite such gains, efforts to promote black history between the end of World War II and the early 1960s often faltered on the back of white intransigence. However, the growing appeal of black nationalism, the emergence of Black Power, and the impact of urban uprisings in cities such as Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles led to a spate of handwringing from white liberals and a renewed interest in black history as a societal safety valve. For Robert Harris, the result was a groundswell of interest in the African American past, which “permeated practically every sector of American society.”12 As detailed in chapter 4, efforts to establish black studies programs on college campuses across the country became one important part of this trend, with the “long hot summers” prompting an outpouring of new scholarship on race relations and the black experience. In a later study of black historians and the historical profession, August Meier and Elliott Rudwick argued that by the end of the 1960s, Afro-American history had become fashionable, “a ‘hot’ subject finally legitimated as a scholarly specialty.”13

In the realm of national politics, the House of Representatives’ Committee on Education and Labor sponsored hearings to establish a National Commission on Negro History and Culture, which would promote efforts to collect and preserve “historical materials dealing with Negro history and culture” and investigate the possibility of a national museum of black history and culture.14 A bevy of black intellectual and historical experts lent their

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1684)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1608)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1540)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1443)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1402)

Tip Top by Bill James(1400)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1359)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1342)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1337)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1322)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1297)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1290)

F*cking History by The Captain(1284)

American Dreams by Unknown(1272)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1249)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1244)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1199)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1164)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1111)